After the festive season many employers will be left in the dark regarding the whereabouts of some of their employees that have failed to return to work. Did the employee find another job or is the employee absent as a result of illness or other circumstances?

The reality is that the employer will not know and can therefore not assume that the employee has no intention to return to work. In such circumstances the onus rests on the employer to establish whether the employee will return to work or not before termination of employment may be considered.

The Oxford dictionary defines the word ‘abscond’ as leaving hurriedly and secretly. It can therefore be said that the act of absconding means that one does not have the intention to return to work. In circumstances where the employer does not know whether the employee will return to work or not, the employer will have to establish this before the employee can be dismissed. It is therefore common practice that un-communicated and unauthorised absence for a period of more than three days will be dealt with as absconding as per most disciplinary codes.

Communicated absence from work cannot be dealt with as abscondment, since the employee indicated his/her intent to return to work by informing his employer of his whereabouts.

In Pick ’n Pay Retailers (Pty) Ltd v South African Catering Commercial and Allied Workers’ Union obo L Mzazi (case number CA 19/2015) the employee was absent from his work without the permission of his employer. The employer sent two telegrams to the employee. The first on 28 December 2012 and a second one on 2 January 2013. Both were sent to an incorrect address in Mfuleni, Cape Town. In these telegrams the employee was informed that he had been absent without authorisation and had not communicated the reasons for his absence. He was asked to contact the employer regarding his absence from work and informed that a failure to do so may lead to disciplinary action. On 11 January 2013, a third telegram sent to the same incorrect address recorded that a disciplinary hearing would be held on 15 January 2013 and that the hearing may proceed in his absence if the employee failed to attend. The employee did not receive any of the three telegrams. On 15 January 2013, the disciplinary hearing was held in the absence of the employee. The written notice to attend the disciplinary enquiry recorded that the notice had been “issued in absentia” to the employee. It stated that the hearing related to “absconding from your workplace since 22/12/12 without authorisation”. The initiator of the disciplinary enquiry relied on the three telegrams sent to the employee, an absenteeism report and an attendance register. The minutes recorded that the employee had waived his rights to lead evidence at the hearing. In his closing argument the initiator reiterated that the telegrams had been sent to the employee who had been absent from work and who “… clearly has no interest to work and should be found guilty”. The chairperson proceeded to find the employee “guilty of absconding from the workplace”. The aggravating factors relevant to sanction put up by the initiator were the severe negative impact that absconding from the workplace had on the appellant’s business, the shortage of staff causing poor service delivery and the employee’s failure to respond to the telegrams sent to him. He stated that the employee’s behaviour could not be condoned and indicated that the employee “is not interested in his work”.

The employee was dismissed with immediate effect. On his return to work on 4 February 2013, the employee was informed of his dismissal. Aggrieved with the decision to dismiss him, he referred an unfair dismissal dispute to the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA). The evidence at arbitration was that the employee approached the initiator on 21 December 2012, at a time when the store manager was with him in the office, with a request to take leave from 27 December 2012. When the employee told him that he had been granted leave, the initiator indicated that he was not aware of this:

… he said, “I have to take my leave and I’ve got leave.” I said, “Well, yes you’ve got leave, we can talk about when you need to take leave but I think it’s not fair for you to just come to me now and you’re telling me you’re taking leave from the 27th or whenever … the store manager was in the office at that point in time, so then I said okay, fine, I will give you leave not now because one, I need to make a plan to get someone in your position. Secondly, it’s just a bit of a short notice for me considering the time of the season.

The initiator told the employee that he could take leave in the first week of January; that he should come to him so that the paperwork could be completed; and that the employee should ensure that someone was available to work in his place.

In the arbitration award, the commissioner rejected the employee’s version, finding that he had taken leave without authorisation and that he had committed misconduct. The commissioner took account of the employee’s key position, his lengthy period of unauthorised leave, the fact that it was taken at the busiest retail time of the year and his failure to reach an agreement with his employer regarding leave in January or occasional leave. This led the commissioner to conclude that the misconduct committed was serious, had implications for the employer’s operations and undermined the trust relationship. Although the commissioner found that the employee had no intention to abscond which “placed his conduct in a different light” to what was found at the disciplinary hearing, given his lengthy absence from work and his lack of contact with his employer, the employer “had no choice” but to assume that he was not returning to work. The dismissal of the employee was accordingly found to be substantively fair.

Turning to the procedural fairness of the dismissal, the commissioner found that the appellant “should have dealt with the situation differently when the applicant eventually returned to work” and given him a hearing on his return to work:

The fact that the applicant did return to work, and reported for duty, meant that there was no intention to abscond. This placed his conduct in a different light. While the absence of the applicant was lengthy, the applicant also had a long service history with the respondent. The respondent is a large employer with a sophisticated and well-resourced HR department. The applicant was entitled to the very basic principle of fairness … to state [his] side of the matter, and to defend himself against allegations of misconduct.

The employee was awarded two months’ compensation for procedural unfairness. On review, the Labour Court took account of the fact that the commissioner found that the employee had not absconded from work, which was the offence he had been charged with, as well as the commissioner’s finding that this placed the employee’s conduct “in a different light”. The Court found that “it can be assumed” that the commissioner’s finding that the employee should have been provided with a proper opportunity to explain his conduct on his return meant that had such opportunity been provided “this may have prevented his dismissal”. Furthermore, it was noted that:

The issue of [the employee’s] clean disciplinary record, the reason for his need to return to the Eastern Cape to unveil tombstones for his parents and [his] relatively long employment history with the company were all considerations that should have been addressed by the Commissioner in the process of coming to a decision regarding the substantive fairness of the dismissal. They were not. Further, the reasoning that a disciplinary hearing may have put [his] absence in a different light, highlights the flaw in this approach.

The Court found that the decision that the dismissal was substantively fair was one that a reasonable decision-maker could not reach. No issue was taken with the commissioner’s finding that the dismissal had been procedurally unfair.

In its notice of appeal in the Labour Appeal Court, the employer raised the following broad grounds of appeal:

- That the Labour Court erred in finding that the commissioner’s decision that the dismissal of the employee was substantively fair was not one that a reasonable decision-maker could make.

The Labour Appeal Court placed emphasis on corrective and progressive discipline as per Schedule 8 of the Labour Relations Act. The Code of Good Practice recognises that dismissal for a first offence is reserved for cases in which the misconduct is serious and of such gravity that it makes continued employment intolerable. For leave without authorisation to justify summary dismissal for the first offence, the material before the commissioner must exist to show that the misconduct was of such a serious nature as to justify dismissal the imposition of the most severe of available sanctions. Although it was suggested that the employee’s absence caused operational strain over the busy festive period given his position as storeman, no evidence showed that it caused harm of such a serious nature that it warranted summary dismissal for the first offence. This was more so when the employee had a lengthy period of service and a clean disciplinary record. While he was clearly wilful and displayed disregard for the employer’s rules, the employee was not dishonest in his misconduct, which was shown to have caused inconvenience but no proven loss or damage to the employer. Regard was not had by the commissioner to the fact that, as a large employer, the company had the resources to make contingency plans, that such plans were made, and that the employee ultimately returned to work at the conclusion of what he considered to be the leave days due to him. Furthermore, the commissioner did not have regard to the appellant’s evidence of its failure to comply with its own procedure in sending telegrams calling on an employee to return to work to the incorrect address. The fact that the appellant did not comply with its own procedure made it irrelevant whether the employee would have complied with the instruction to return to work if the correct address had been used.

The Labour Court’s finding could not be faulted that the commissioner’s decision that the dismissal of the employee was substantively fair was not one that a reasonable decision-maker could reach on the material before him. The appeal failed.

From the above it is evident that employers should not act hastily in terminating the employment of employees, even for extended periods of absence from work. The fact that the employee returned to work should have prompted the employer to instead deal with the extended absence from work as unauthorised and unjustified absence. The employee should also have been given an opportunity to defend at an appeal enquiry before a final decision was taken about his continued employment.

So how does one establish whether the employee intends to return to work?

Step 1

The onus will be on the employer to enquire about the whereabouts of the employee and to instruct the employee to return to work. This is normally done as follows.

- Stop paying the employee. The employer does not have to pay the employee if the employee failed to report for duty without permission or justification. Employees are quick to make contact with the payroll office when they are not paid on the normal payday.

- Call the employee on his cell phone. It is surprising that many employers fail to do this and skip straight to sending a letter by registered mail. Note the date and time of the call and when messages were left.

- Enquire with friends at work and family members. Note their comments.

- Ensure that an obligation is placed on employees to inform the company of any changes to their residential and/or postal addresses. Employees must understand the consequences of not updating such information.

- Send a letter to the employee (see example below) by registered mail or deliver it to the last known address of the employee.

Dear Employee

You have been absent from work without permission since 5 January 2022 and failed to communicate your absence to the company. You are instructed to return to work immediately. Failure to do so will lead us to believe that you have no intention to return to work and may lead to your dismissal.

If you do not return to work on the xxx of January 2022 a disciplinary hearing will be held which may lead to your dismissal.

Signed

The Employer

6. Deliver the letter to the residential address of the employee or send it by registered mail. Make sure that proof of delivery is obtained. WhatsApp communication may also be used as long as

there is proof of transmission, delivery and confirmation that the message was seen.

The question now is what to do if the employee fails to report for duty on the stipulated dated?

Step 2

The employer will have to follow-up the first letter with a notification to attend a disciplinary enquiry. The employee will be charged with abscondment with an alternative charge of unauthorised absence from work for an extended period.

An important point to remember is to remind the employee of the consequences of non-attendance. If the employee does not attend the hearing it will commence in absentia. If the employee appears at the enquiry, he will have to justify his absence from work.

Step 3

If the employee is dismissed in absentia, a third letter will have to be served on the employee confirming the dismissal and reminding the employee of the right to refer the matter to the CCMA within 30 days from the date of dismissal.

Justifying the dismissal

But what does one do if the employee decides to return to work after the dismissal? Can one simply indicate to the employee that he was dismissed and wish him all of the best for the future? The answer is no. The employer must first give the employee the opportunity to be heard. It is not necessary to convene a fresh disciplinary hearing, the employee can just be given the opportunity to appeal against his or her dismissal, citing reasons for the extended period of absence.

This may pose a new problem for the employer since the employee may have valid and reasonable justification for staying away from work and not responding to the requests of the employer to return to work. The employer will be required to carefully evaluate the dismissal of the employee and must be able to prove that:

- Attempts were made to get the employee back to work.

- The employer allowed a reasonable period before dismissing the employee.

- The period of absence from work was unreasonable when weighed up against the operational requirements of the company, the importance of the position and the impact on other employees.

- And the length of service, remorse, necessity and other mitigating factors are weighed up against the seriousness of the misconduct in totality.

It may prove to be a costly decision for an employer that opts to rush to make the most of such a window of “opportunity” to get rid of a troublesome employee.

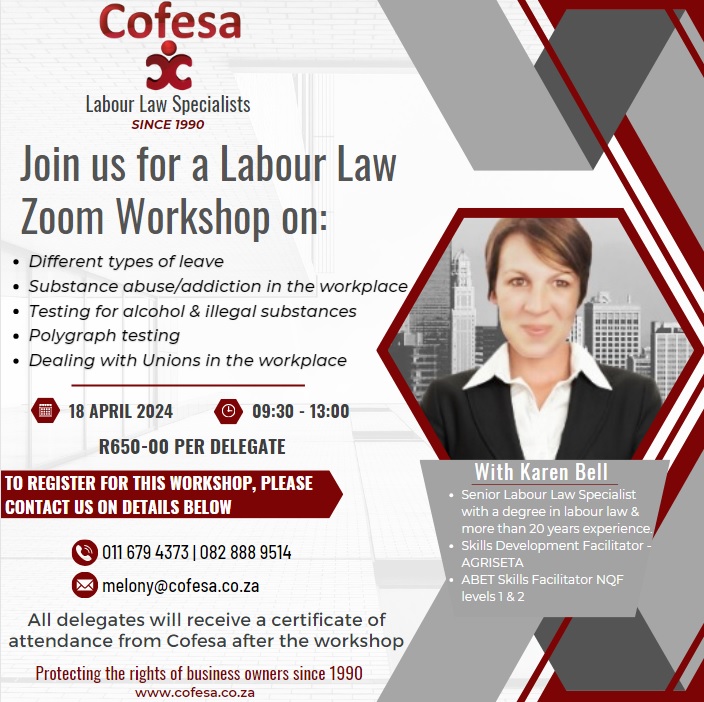

CONTACT THE COFESA 24/7 HELPLINE TO ENSURE YOU FOLLOW THE CORRECT PROCEDURE AT ALL TIMES

011 679 4373 | 082 656 4957 | etienne@cofesa.co.za

Source: Labourguide | By Jan du Toit