Poor work performance, or incapacity, is dealt with in Schedule 8 of the Labour Relations Act no. 66 of 1995, and refers to the inability of an employee to perform in terms of the employer’s expectations pertaining to quantity, quality or both. Such inability to perform is normally as a result of circumstances beyond the control of the employee.

Item 9 of Schedule 8 (Code of Good Practice: Dismissal) of the Labour Relations Act deals with the guidelines in cases of dismissal for poor work performance and provides as follows:

Any person determining whether a dismissal for poor work performance is unfair should consider—

(a) whether or not the employee failed to meet a performance standard; and

(b) if the employee did not meet a required performance standard whether or not—

(i) the employee was aware, or could reasonably be expected to have been aware, of the required performance standard;

(ii) the employee was given a fair opportunity to meet the required performance standard; and

(iii) dismissal was an appropriate sanction for not meeting the required performance standard.

Item 8 (2), (3) and (4) of the Schedule provides (in reference to employees under probation) inter alia that after probation, an employee should not be dismissed for unsatisfactory performance unless the employer has—

(a) given the employee appropriate evaluation, instruction, training, guidance or counselling; and

(b) after a reasonable period of time for improvement, the employee continues to perform unsatisfactorily.

The procedure leading to dismissal should include an investigation to establish the reasons for the unsatisfactory performance and the employer should consider other ways, short of dismissal, to remedy the matter.

During this process, the employee should have the right to be heard and to be assisted by a trade union representative or a fellow employee.

Section 188 of the Labour Relations Act provides, furthermore, that if a dismissal is not automatically unfair, it is unfair if the employer fails to prove –

(a) that the reason for dismissal is a fair reason related to the employee’s conduct or capacity; or based on the employer’s operational requirements; and

(b) that the dismissal was affected in accordance with a fair procedure.

In his book titled “Workplace Law” (12th ed., Juta, 2017) from page 25 onwards, Professor John Grogan states the following regarding the essentials of the contract of employment:

- It is a voluntary agreement;

- There are two legal personae (parties);

- The employee agrees to perform certain specified and/or implied duties for the employer;

- Their contract endures for an indefinite or specified period;

- The employer agrees to pay a fixed or ascertainable remuneration to the employee;

- The employer gains a (qualified) right to command the employee as to the manner in which he or she carries out his or her duties.

In Sun Couriers v CCMA and others (2002) 23 ILJ 189 (LC), the Court noted when employees enter into contracts of employment, they impliedly undertake to work according to reasonable standards set by their employers. Any employer has the right to establish reasonable requirements in terms of the output and the standard of work required of the employee.

In Boss Logistics v Phopi (2010) 31 ILJ 1644 (LC), the Court set out the relevant factors to be considered when determining whether the employee has been afforded a reasonable time to comply with the required standards. The Labour Court found that the said relevant factors are the complexity of the job, the volume and nature of the work, the nature of the employer’s business, and the qualifications and the experience of the employee.

In Somyo v Ross Poultry Breeders (PTY) Ltd [1997] 7 BLLR 862 (LAC), the Court held as follows;

“An employer who is concerned about the poor performance of an employee is normally required to appraise the employee’s work performance; to warn the employee that if his work performance does not improve, he might be dismissed; and to allow the employee a reasonable opportunity to improve his performance.”

According to Professor John Grogan in his book titled “Dismissal” (3rd ed., Juta, 2020) from page 445 onwards, proof of poor work performance is best offered in the form of an objective assessment or appraisal of the employee’s work. The reason for why the assessment must be “objective” is obvious: if the decision were to be left entirely to the subjective judgement of employers, their word would be beyond judicial scrutiny. As in many other areas of law, the test whether an employee has failed to meet a performance standard cannot always be shorn entirely of subjective considerations. In some cases, it may not be difficult to prove a failure to achieve required output levels. However, where work entails the exercise of some discretion by the employee, it may be more difficult to prove such deficiencies as “poor judgement” on empirical grounds.

In conclusion, we recommend that employers should develop clear policies on poor work-performance procedures. Employers should also establish reasonable and realistic performance standards, which can be achieved by employees. In addition to their contracts of employment, employees must be required to enter into performance agreements. Employers are also advised to regularly review and assess the performance of employees and to embark on formal incapacity procedures without delay. Such processes must be in accordance with the guidelines set out in Schedule 8 of the Labour Relations Act.

Lastly, we recommend that employers procure the services of suitable and experienced chairpersons to preside over incapacity hearings.

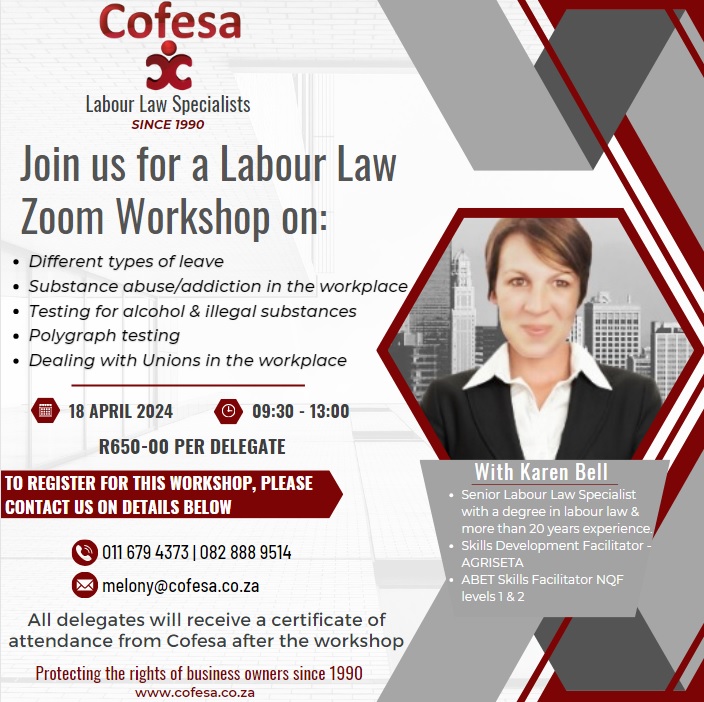

CONTACT THE COFESA 24-HOUR HELPLINE FOR ASSISTANCE

011 679 4373 | ETIENNE@COFESA.CO.ZA

Source: www.labourguide.co.za | By Magate Phala | Magate Phala is a labour law specialist and founding director of Magate Phala & Associates